08 Aug Ketchup, Catsup and Dogsup

What is there to say about ketchup? A lot, it turns out, as ketchup is probably the most American of condiments. Mustard has German origins, mayo from the aioli of France, hot sauce is worldwide, and bbq sauce wouldn’t even exist without ketchup. But the ketchup we know, use and love today, is a mere peek into the world (and possibilities) of ketchup.

The British, while traveling the world ‘looking for spices’ (lets use this euphemism for the sake of this discussion of food, not ignoring or washing over the harsh realities of the world at this point in history), came across ke-tsiap in China. Ke-tsiap was the word used for fermented fish in a certain part of China at the time. The British took this idea home with them and used the method, salting and fermenting, to create new foods. Mushrooms, green walnuts, and anchovies were some of the earliest experiments with this method in western cuisine, with at least mushroom ketchup still commercially available in the U.K.

As the immigration to America continued, so did the building of its culinary identity, brick by proverbial brick. This culinary identity is still being built, through immigration, education and the pleasure derived from eating both new and delicious things. As ketchup made its way to the Untied States, ingredients and methods evolved. While there are still recipes for fermented ketchups in early American cookbooks (most notably in the Joy of Cooking), at some point there was a change in how it was made. Instead of fermenting a product for its flavorful liquid extract, fermented wine (vinegar) was added to the main ingredient, cooked along with spices and sugar to tame the acidity of the vinegar. Early ketchups in the U.S. include grape, cranberry and prune.

The industrial revolution led to the ketchup we know of today. As tomato canning methods became viable and popular, so did tomato ketchup. This bit of historical serendipity was great for tomato ketchup but began the decline of other flavored ketchups. While you can still find other ketchups (the vinegar/sugar kind, not so much the fermented kind) to purchase commercially, tomato ketchup has clearly won the ‘market space’ (and culinary space) battle.

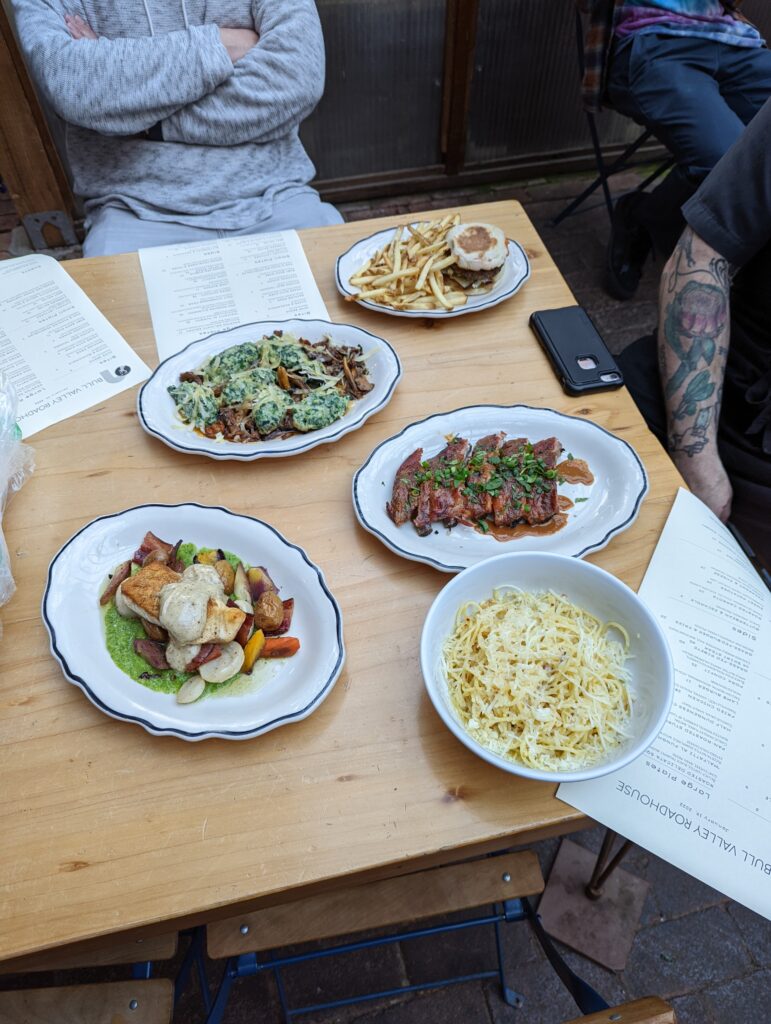

As a fan of food, culture and eating, this saddens me. So, while we offer tomato ketchup with our burgers and fries at Bull Valley, we also scratch our intellectual (and gustatory) itch by making other ketchups. We make an old fashioned mushroom ketchup (mushrooms salted at 10% mixed with spices left to ferment for 2-3 weeks) that we use in a grass fed steak tartare dish (with celery root remoulade, black pepper aioli, generous amounts of chive and some spelt bread from acme bakery). We have been making apple, and now pluot ketchup for our thinly sliced pork chop dish (just like the traditional pork chops and apple sauce, but a little more interesting) for a bit now.

I often think that menu language is often disappointing and at times lazy and inconsistent. Why on earth is the word ‘calamari’ on a non-Italian food menu? So, when thinking of how to construct the food and menu aesthetic of the Bull Valley Roadhouse, I take a cue from the setting (the building and town) as well as being consistent with Tamir’s approach to the expertly crafted cocktails (with a nod to history, everything done intentionally, and of course made to be delicious) to form a cohesive whole.

Post Script: I prefer the more modern ‘ketchup’ over the more antiquated ‘catsup’. There is also evidence in old American cookbooks of it being called ‘dogsup’ and a reduced version called ‘double dogsup’ and as funny as that is to me, it’ll have to exist in my brain’s humor center rather than practical usage. And despite what Ronald Reagan’s FDA said, ketchup is not a vegetable.